Balancing act between esthetics and acoustics

How we perceive a room depends on its materials, its proportions, the light … and the acoustics. Unlike visually perceptible elements, building acoustics are not immediately obvious. This has a significant impact on the work of acousticians like Clemens Kuhn-Rahloff.

Author: Fabian Baer

Photography: Lindner Group, Helene Hoyer Mikkelsen

“In a sense, there is always a trade-off between esthetics and acoustics. Nevertheless, as much thought as possible needs to be given to the flexibility of use of a room and, of course, building acoustics are part of this,” as Kuhn-Rahloff knows from his many years as an acoustician at the engineering firm Gartenmann Engineering AG.

The fact that there are sometimes conflicting goals between the various disciplines is in the nature of things, he says, because sound insulation requires space and a specific wall structure. “This is combined with the fact that building acoustics often rely on special materials such as perforated surfaces, microperforated glass walls, or sound-absorbing textiles.” Often, he explains, it’s a question of how far the use of these special, functional materials fits in with the building’s design concept and layout, since architects have a strong visual focus. “And let’s not forget that building acoustics are always a question of money.”

Sharp increase in requirements

Nevertheless, he notes that the requirements for building acoustics have risen sharply in recent decades, both in Switzerland and internationally. “The first investigations into sound insulation in buildings were carried out in the 1950s and 1960s to find out what sound insulation values could be achieved with typical constructions and how users perceived them.” Over the years, and with the general increase in building standards, this has developed into a set of norms and regulations that in part define legal requirements, but also simply make recommendations, depending on the level of quality required. This includes provisions for airborne sound insulation, impact sound, and building services noise. Even though regulations for noise protection may differ from country to country, the basic principles in terms of structure are comparable, according to Kuhn-Rahloff.

“The focus has changed, our need for

privacy is much greater today.”

Tailored to the building’s use

Asked at what point building acoustics should ideally be included in the planning of buildings and rooms, Kuhn-Rahloff is very clear: “For more complex buildings, it should form part of the utilization concept from the very outset. It is at this early stage that the building acoustics, as well as sound insulation and the overall standard of finish, can be best considered. One way or another, building acoustics must always be tailored to use,” he says, adding that good sound insulation is not simply the absence of unwanted sound, but also the control of wanted sound.

Noise or not?

When we talk about wanted or unwanted sound, the question naturally arises about the definition and nature of noise. According to the acoustician, “Noise is always unwanted sound, but this depends on the situation, the context, and above all individual perception. The effects of noise from roads, railways, and airplanes are well studied and understood, but this is much more difficult to do in the case of everyday noise. In open-plan offices, for example, even intelligible speech has a very disturbing effect.” Noise is less a question of loudness, but rather of the disturbance it causes, which can manifest itself as a sense of annoyance or even a physiological disorder if it is very long lasting. At the same time, it is not necessarily pleasant to be in a room if it is acoustically dead, he explains.

Building acoustics and room potential

If you ask an acoustician to draw a room with the best possible acoustics, the result, according to Kuhn-Rahloff, is a room that is not necessarily architecturally versatile. However, when talking about the different characteristics of a room and the corresponding effects on acoustics, he expresses a more nuanced view: “High or large rooms are not bad for acoustics per se. Again, it’s about the pur-pose and the acoustic properties that a room is supposed to have.” He is also hesitant to give a blanket answer to the question of whether openings are bad for building acoustics: “Of course, the boundaries of physics can’t be pushed. But even passageways that are intentionally left open can be optimized, for example by using absorbent elements on ceilings and walls. In this case, the longer and bigger the better.”

Even better, however, is the use of a door, where soundproofing plays a key role. For complete privacy, doors with stop and drop-down seals are required. With sliding doors, a great deal of effort is necessary to ensure that these requirements are also met. “Even small gaps in the seal are clearly noticeable and, if it is not fitted correctly, you can hear it quite quickly,” explains Kuhn-Rahloff. The choice of door leaf is crucial, he says: “With high requirements, such as noise protection of over 30 dB, you have to think very carefully about what kind of door leaf to use.”

Auralization as a tool

One of the biggest challenges in ensuring reliable building acoustics is that acoustics cannot be visualized. This is where auralization comes into play. “This is an established means of assessing the acoustics of a room and uses a computer model to allow us to hear the acoustics. Broadly speaking, the room that an architect has planned is recreated in the computer and various acoustic materials are added. This makes it possible to listen to the future acoustics of a room in different positions,” explains the acoustician.

Auralization has been used in concert halls for many decades, but for building acoustics it is still quite new and innovative, particularly in the sense that it can be taken to a client meeting and demonstrated. “For sound insulation, auralization is mainly used to give the client an impression of what is still audible from the neighboring room.” Specifically, the sound insulation of the partition wall can be selected on the computer, so that different insulation levels can be demonstrated to the client. For Kuhn-Rahloff, the rise of auralization in the field of building acoustics supports his vision as an acoustician: “Architecture for everyday spaces should always be acoustic architecture. Rooms essentially need an acoustic quality that is congruent with the visual character.”

Clemens Kuhn-Rahloff

Clemens Kuhn-Rahloff studied in Berlin and Paris and received his doctorate in acoustics from the Technical University (TU) Berlin. He is a partner at the engineering firm Gartenmann Engineering AG in Zurich and Bern. As a sound engineer, he has several years of professional experience in music production. He is a part-time lecturer at Zurich University of the Arts and at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland.

Understanding Acoustics

Building acoustics deals with the effects of structural conditions on sound propagation between rooms within a building or between the interior of a building and the outside world. By contrast, room acoustics deals with the structural conditions of a room and the sound events that occur within it.

In order to quantify and assess sound (insulation), there are various options and measurement methods. Hawa measured the sound propagation from a sending room to a decoupled receiving room in a sound laboratory. A wall and a built-in sliding door with the Hawa Junior Acoustics and Hawa Porta Acoustics hardware acted as room dividers for the room-to-room measurement.

Weighted sound reduction index Rw

Rw is the weighted sound reduction index in dB of a building element. Rw includes the sound transmission through the component without the influence of adjacent components.

Building sound insulation index R’w

R’w is a field measurement when the component has been installed in the building. It also takes into account side paths or structural inaccuracies.

Calculated value Rw,R

This is the weighted sound reduction index Rw minus a reduction which allows for differences in the Rw between the objects tested in the lab and the actual conditions on site (e.g. component variations). In Germany, according to DIN 4109, the allowance value doors is 5 dB.

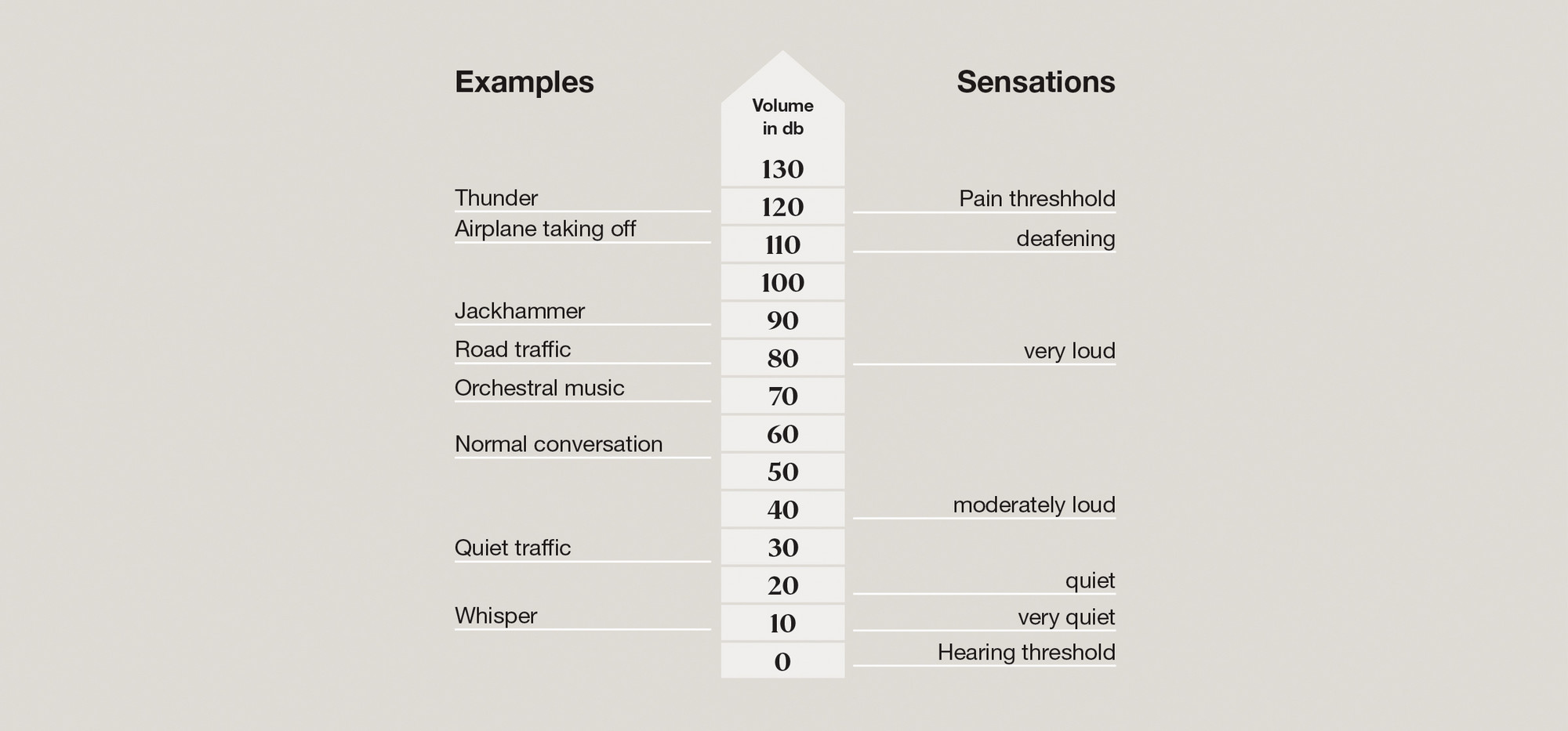

Noise is defined as any sound that is disturbing or damaging to the human hearing ability or the environment. Noise is a very subjective sensation rather than an exact physical concept. It always depends on context and individual sensation. For example, we may find even a normal conversation at 50 dB in an open-plan office to be very distracting and uncomfortably loud, while we enjoy listening to loud music at 80 dB.

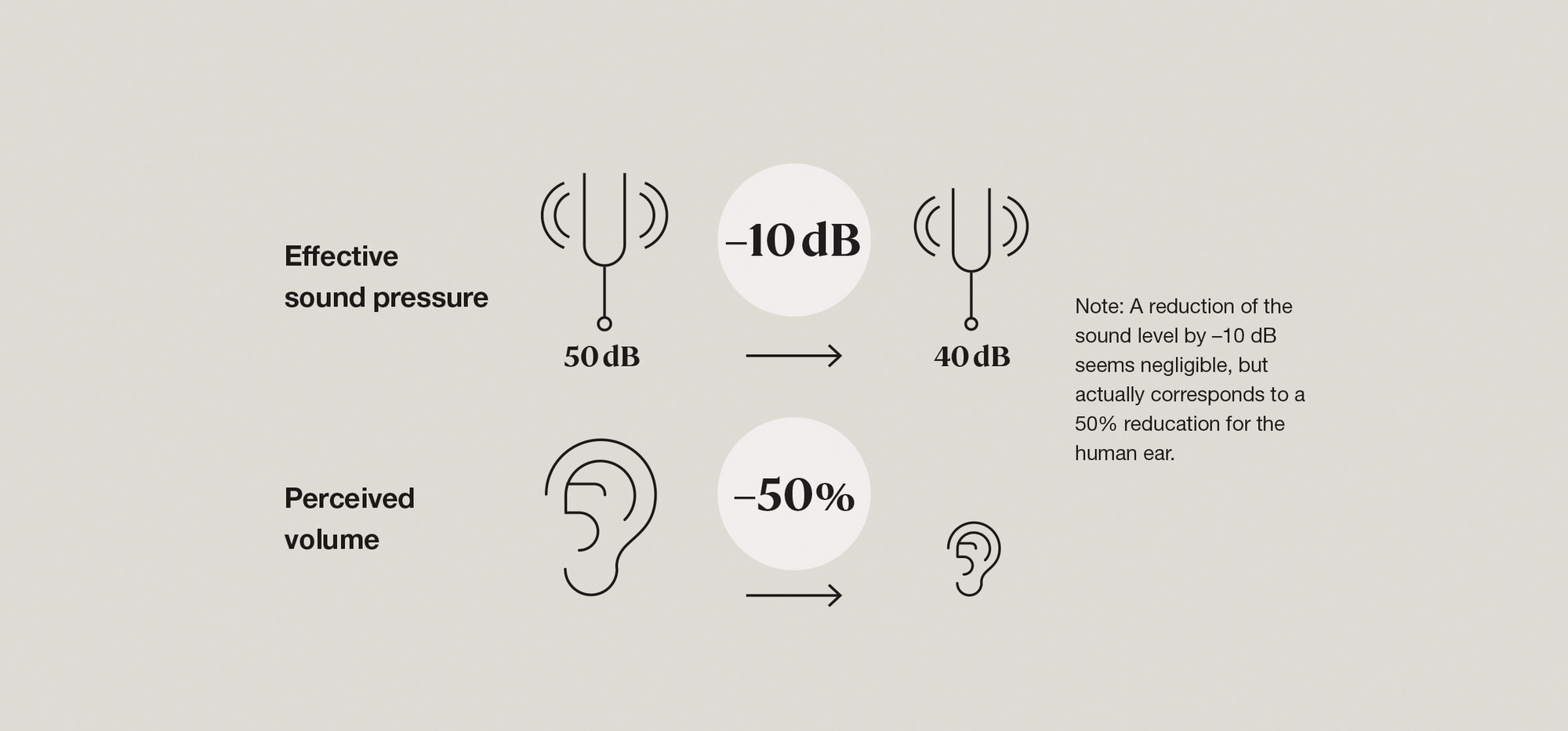

The inventor Graham Bell was the first to discover that the scale of sound perceived by the ear is logarithmic. This logarithmic scale of the sound intensity ratio adapts to the intensity perceived by the human ear. The unit of measurement is a decibel (dB).

Room separation and acoustic solutions

During the recent pandemic, many people came to realize how much they are bothered by noise. Having peace and quiet for work and hobbies is essential.

Read more

Sliding solutions with sound attenuation

Life also means: living together. And more and more of this is taking place in rooms. We live, work, eat, laugh, discuss, sleep and dream together. However, everyone needs a quiet zone. This is always within reach with sliding solutions from Hawa Sliding Solutions.

Learn more